Great Lives – February/March 2023

In February and March we discovered Mary Somerville (1780-1872). She lived at a time when it was believed that education made women morally and physically unfit for motherhood. Yet she was a wife and mother, and by her own efforts became a leading expert and gifted writer in many branches of science and was honoured throughout Europe.

Born Mary Fairfax in Jedburgh, church manse – home of Mother’s sister Martha and husband Thomas Somerville. Mother: Margaret Charters – well-to-do Scottish family, but had no money of her own. Father: William Fairfax – naval officer, rose to rank of Admiral and knighted, but not wealthy. Earned modest salary from service in American War of Independence and in British services overseas. Mary fifth of seven children: three died young. Brother three years older, a younger sister and younger brother.

Mary was brought up in the family home in Burntisland on Firth of Forth, not far from Edinburgh. The family lived in “genteel poverty” and Mary was allowed to run pretty wild in coastal countryside around the home and, like her father, became fascinated by natural history. He was passionate about flowers, especially tulips, and Mary studied seashells, birds and flowers.

Her two brothers were given a good education. There was no money for a tutor or governess for Mary – not thought to be important anyway. By the age of eight, she could read, taught by her mother, but not write.

When 10, her father came home from sea and described her as a savage. She was sent for one year to Miss Primrose’s boarding school in Musselburgh. After year, she could read and write, but not very well, do simple arithmetic and speak a little French. On leaving, she said she felt “like a wild animal escaped out of a cage”.

She was taught informally at home – lessons included geography and astronomy. Mary read all the books she could find at home, although discouraged as she felt it to be an “unladylike” occupation. She did find a magazine in the house which was mainly fashion plates, but also contained articles on algebra. She became passionate about maths and looked for books to further her knowledge. She would also listen in when her brother was being tutored in Maths and found she could answer questions which he couldn’t. The tutor was impressed and agreed to teach her informally.

When Mary visited her uncle, she told him she was teaching herself Latin. He encouraged her and they would read Latin before breakfast when she stayed in the Jedburgh manse.

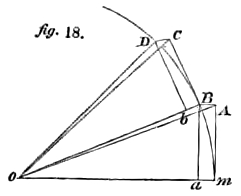

Following her younger sister’s death, Mary was banned from receiving further education – the family felt too much intellectual activity had contributed to her sister’s death. It was felt that “the strain of abstract thought would injure the tender female frame”. The same didn’t apply to brothers. She continued to teach herself in secret. Apart from maths, she was skilled at painting and had lessons at a school in Edinburgh. She learned about perspective, which she found inspiring but mainly from a mathematical sense. She obtained a copy of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry and taught herself from it. She enjoyed Art and impressed one of her mother’s rather grand relatives with her painting. The aunt felt it was lucky that Mary had that skill – she could earn her living by painting. “for everyone knows she will not have a sixpence”.

Mary was expected to fulfil her female role in her well-connected family and join in the social life of Edinburgh. She was encouraged – and enjoyed – parties, visits, balls, theatre, concerts, and innocent flirtations. She was said to be sweet and polite and dubbed “Rose of Jedburgh” in social circles. Not just an intellectual swot.

Luckily, Mary was born into the age of Scottish Enlightenment.

As a young debutante in Edinburgh, she sought out friends of her brother and father, begging them for more lessons in Latin, algebra, geology and natural history. She was now moving among Edinburgh’s intelligentsia.

In 1804, at 24, she married a distant cousin, Samuel Greig, who held the post of Russian Consul in London. He did not approve of intellectual pursuits. She had two sons. Perhaps it was lucky for her and science that Greig died only three years after the marriage. She returned to her family in Burntisland, an impoverished widow with two infants, one of whom she was still nursing.

That didn’t stop her learning. Before she began her duties as a mother and daughter, she rose early in the morning to study trigonometry and astronomy and grappled with understanding Newton’s Principia. In Edinburgh, she contacted leading mathematicians of the day, William and John Wallace, and persuaded them to recommend scientific books, all in French, that she used to continue her studies. She also befriended Henry Brougham, then a rising politician who later became Lord Chancellor and founder of the University of London, and she began to make scientific observations of her own.

In 1812 she remarried, this time to a first cousin, Dr William Somerville, nine years her senior. Mary was his second wife, his first wife dying in in 1808. Their only son, Thomas, died in infancy. William also had an illegitimate son born in 1806, whom he fully supported and helped train as a doctor. He died in 1847. He was a naval physician – and his marriage to Mary was a very happy one.

She took no notice of people who disapproved loudly of her work and described her as eccentric and foolish. She was proud of her achievements He encouraged her scientific research – fitted around the birth of four more children.

William became Fellow of the Royal Society – she could only enjoy an honorary position as women were not admitted. Early in her career she wrote a paper “On the Magnetizing Power of the More Refrangible Solar Rays” – which had to be read by William as women were not allowed to attend meetings.

She lived in relative comfort in London, with servants, but had her fair share of tragedy: both her sons died in infancy and her eldest daughter, Margaret, died age nine. Also, she had spells of serious illness herself, but enjoyed a good social life among leading writers, thinkers, and liberal politicians of the time.

Her friends and acquaintances included Lady Byron, who had left her husband, poet Lord Byron, soon after their daughter was born. She asked Mary to tutor her daughter, who became Ada Lovelace, one of the founders of computer science. The Somervilles were also friendly with the artist Turner and Mary often visited his studio.

The age they lived in is known as “Age of Wonder”. Following the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was the undisputed great power of the 19th century. It was the first industrial nation and the intellectual life in London was blooming.

Robert Peel started what would become the Metropolitan Police. Capital punishment became limited only to treason, murder and arson. Workhouses were built, schools for the poor, gas lighting, railways and the metropolitan system all began in Mary’s lifetime – all seen as great progress.

In 1827, Mary’s friend Henry Brougham was busy founding his “Society for Diffusing Useful Knowledge”. He asked William to persuade his wife to translate from the French Laplace’s seminal work on astronomy in a way that all could understand it. He felt that only Mary could do it.

She turned this proposal down, but Brougham refused to take no for an answer and travelled to Chelsea to discuss it with her in person. She agreed on condition that if it were not good enough it should be burnt – it was good enough. Mary commented: “Thus suddenly and unexpectedly the whole character and course of my future life changed”. Sir John Herschel, the astronomer, and his wife were good friends of the Somervilles. He read Mary’s book “The mechanism of the heavens” and was full of praise. He wrote to her saying, “Go on thus and you will leave a memorial of no common kind to posterity”.

The book was meant to be part of Brougham’s series of popular educational tracts. But it was too long and was published on its own in 1831 by John Murray. The book became very successful and three years later Mary published her second major scientific work “On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences”. This was the publisher’s most successful book on science until he published Darwin’s On the Origin of Species 25 years later.

In her 50s, when two books were published, she had met with leading scientists in Britain and France: astronomers, physicists, geologists, and chemists, explored wide range of subjects from terrestrial magnetism to giant seaweed. One chapter was based on her own research into infrared and ultraviolent rays – one of the first descriptions of these phenomena.

In one of her books, she discussed the possibility of another unknown planet having an effect on the path of Uranus. This later led to the investigation and discovery of Neptune.

Her books were clearly written and she managed to convey her curiosity and fascinated readers who were not necessarily scientists, by speculated about planets which hadn’t yet been observed and looking at potential future developments including how climate could change and causes of earthquakes.

Her third book was Physical Geography, published in 1848 – the first English language textbook in this area, which introduced a new regional approach to geography. It was on university reading lists, including Oxford’s, for decades. She won many awards, eventually the Victoria Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society. Her contribution to science was so great the she was one of the first two women, along with Caroline Herschel, to be elected as an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Sir David Brewster, inventor of the kaleidoscope, said of her: Mary Somerville was certainly the most extraordinary woman in Europe – a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman. Shame he had to bring gender into it but shows how unusual it was at that time for a woman to achieve so much.

The government rewarded her with an annual pension of £200, increased later to £300. This proved useful, as her husband lost all his money in poor investments.

Around 1838 Mary, her husband and two unmarried daughters, Martha and Mary Charlotte, moved to Italy and travelled all over Europe to meet other scientists and writers. By the middle of the 19th century, women’s suffrage was growing, and Mary actively supported the movement. She agreed to be the leading signatory on a petition for votes for women, which was presented to Parliament more than 50 years before limited suffrage was won in the Representation of the People Act of 1918. William died in 1860 age 92 in Florence.

Even in extreme old age Mary remained interested in scientific progress and studied calculus and kept up with events through the newspapers. She spent 29th November 1872 working on a complex mathematical system and died in Naples in her sleep that night, less than a month before her 92nd birthday.

Seven years after her death, Oxford University opened its second women’s college, calling it Somerville. It was among the first to allow women to attend.

In February 2016, The Royal Bank of Scotland organised a vote to decide which of three notable Scots should appear on its new polymer £10 note. It would be the first time a non-royal would be represented. Facebook joined in the campaign. The three chosen were physicist James Clerk Maxwell, the Civil Engineer Thomas Telford and Mary Somerville. Mary was leading the poll until the last minute when there was a surge of votes for Thomas Telford leaving Mary in second place. However, Facebook and the Bank declared the results void as it was discovered that much of the last-minute surge was from India and other countries so Mary Somerville’s face was used on the £10 note.

Jill Maynard